The genius design choice that reproduces a brand name three trillion times for free

There are estimated to have been over 600 billion LEGO bricks produced over the years¹. And you’ve probably noticed that on each stud on each brick it says “LEGO”.

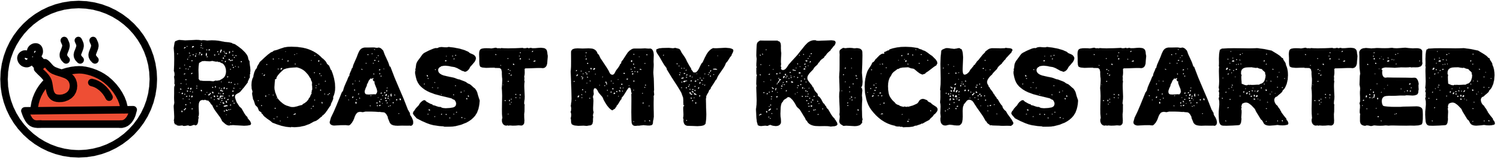

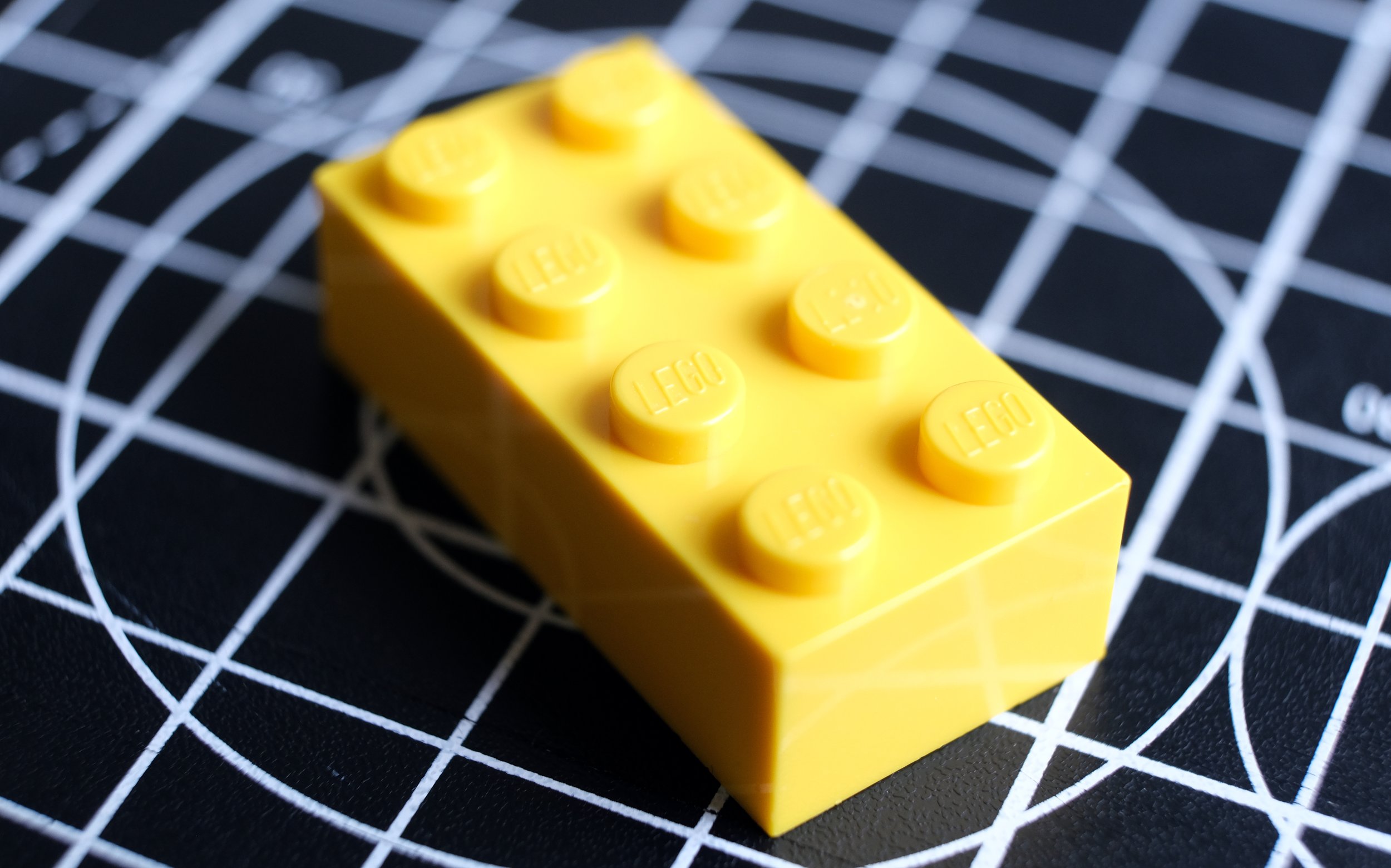

4 x 2 LEGO brickThere’s also a “LEGO” inside most bricks.

Internal details of a LEGO brickI don’t know what the average size of a brick is, but I’d say a 2x2 brick is a reasonable guess. So that’s five “LEGOs” per brick.

For better or worse, most of those LEGO bricks probably still exist. That makes around three trillion tiny three-dimensional instances of the word “LEGO”.

That’s 3,000,000,000,000 - nearly 400 for every person on the planet.

There are probably other words that are found in more abundance printed in books and newspapers, but I can’t think of any other word that’s physically manufactured in those quantities. Maybe something on a coin?

Free branding

As a business, LEGO has pretty amazing brand recognition, and I dare say a part of that is due to the zillions of times millions of people subconsciously read the word LEGO from childhood and throughout their lives.

What’s even more amazing is that it costs LEGO nothing to make their brand name so ubiquitous.

How the company is able to do that is a great example of manufacturing techniques and economies of scale.

Bricks in the mould. [Image: LEGO]Injection moulding

Most LEGO bricks are made by injection moulding ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) plastic². It’s a fairly self explanatory name for a manufacturing technique whereby molten plastic is injected into metal moulds that channel the plastic into the shape of your finished parts.

It’s a process that’s been around for well over a century but it’s still a fairly complicated operation. The moulds are made in different parts that need to be separated at the end, and perfecting things like the wall-thicknesses of the plastic, draft angles, temperatures and optimal flow rates is not trivial. Clearly LEGO are pretty good at it.

It’s easy to take for granted the satisfying snap as any of the billion LEGO pieces is attached firmly to any other. That requires incredible manufacturing tolerances. If any of the bricks were even a fraction of a millimetre out, the bricks could fall apart from one another or be impossible to join together.

ABS is a cheap raw material³ — something like $1.60 per kg, and LEGO probably get themselves an even better price than that! A 2x4 LEGO brick weighs just over 2g so the material cost is a fraction of a cent per brick. Definitely not nothing, but you can imagine there’s a healthy gross margin in there for the business.

Other than the plastic itself, there’s the cost of the tooling and the machines that do the injection moulding. Those aren’t cheap, especially when you consider the precision required from the high-grade steel moulds that are potentially used for hundreds of thousands of parts.

But again, if you spread the cost of the machinery over the number of parts made from it, the finished parts are still dirt cheap.

“LEGO”

So back to the word LEGO.

Machining that into the mould tools adds a small margin of complexity to making the mould, but that’s a one-off cost and over the lifetime of the tool that becomes virtually nothing. And you can assume that LEGO know how to add those details to the parts without messing things up!

There would be other ways to get a similar result. For example you could screen print “LEGO” onto each brick once it was made. Or you could laser engrave it. But those would add significant cost to the process. The genius design choice was to take advantage of the primary manufacturing method used to make the bricks and get “LEGO“ literally built-in for free.

Right tool for the job

Adding the “LEGO” detail to all their bricks is only free because of that particular manufacturing technique and the vast number of identical parts made. If you asked LEGO to make you ten of a custom part with a different word on the studs using the same technique they’d laugh at you.

When making anything there are always different ways of getting things done, and always trade-offs.

If you’re making millions of exactly the same plastic part then injection moulding is the way to go. If you’re making one of something then you might 3D print it, or even carve it by hand.

Then there are plenty of options in the middle. For example if you’re making a relatively small batch of something you might still do a lot of manual assembly, but you could invest in a jig to line up parts. That incurs a small upfront cost but over time you speed up the assembly process and therefore save money.

It usually comes down to how many of a particular thing you’re making, and it’s also a function of cashflow. Can you afford a big upfront cost for expensive machinery?

Even for the same product, there can be an evolution in manufacturing as a product matures. It might not even be a change in the manufacturing method, rather, you move from outsourcing production to doing it yourself. I wrote recently about minimum order quantities (MOQs) and it’s all interconnected.

Choosing the right option

It’s not always obvious what manufacturing option is the right one for your product.

As I said, finances are always a factor. Do you need to raise a chunk of money up front to make your production viable? Of course, crowdfunding can be a great way to do that. Or, initially at least, there may be an element of outsourcing so you don’t need to invest in expensive equipment yourself.

Another variable is how sure you are that a part or a finished product won’t change. You might have to balance design flexibility with unit cost.

The over-simplified graph below shows how injection moulding a part would be prohibitively expensive at low volumes but becomes much cheaper as you make more. Contrast that with 3D printing, which makes sense at low volumes but where the unit price doesn’t really ever come down much. The graph would also keep going far off to the right so the difference is further amplified.

Simplified unit cost vs number of parts madeOf course, price isn’t the only thing to think about. The tight tolerances and strength required from a LEGO brick would be hard to match with 3D printing. Even if you could achieve that with 3D printing it would make that green line higher because it would be pushing the limits of the technique.

…

Picking the best way to make something can be a difficult decision and can feel like a moving target. 3D printing is an example of a technology that’s evolving fast, and what might not have been viable a few years ago now is.

When deciding how to make something, there are plenty of things to think about: material qualities of the finished part/product; unit cost based on your projected volumes; number of variants of your product; how much your design might change over time.

In practice, a lot, if not most, manufacturing is outsourced to some extent, so you’re looking for manufacturing-as-a-service rather than having to chose what factory machinery to invest in directly. But you still need to understand the options.

As well as 3D printing, there are plenty of examples of modern manufacturing that open up whole new worlds of product development. Digital printing technology for example now enables you to make a handful of custom tote bags or t-shirts whereas a few decades ago a supplier wouldn’t have considered making fewer than hundreds or thousands at a time.

New manufacturing options have even opened up whole new business models. Nowadays you could set up an ecommerce website offering print-on-demand (POD) products like baseball caps or posters with almost no upfront capital investment needed. Margins would be small, but if you’re lucky you might make a profit.

Whether you’re making one-off bespoke products, or you’re the new LEGO making millions of the same part, or something in between, you need understand the options available when it comes to manufacturing.

There are always many variables that you need to balance against each other, but if you make the right choices you can create a great product and a great business, and even reproduce your brand name a trillion times for free.

…

Notes

¹ https://ipo.blog.gov.uk/2016/12/13/the-message-is-the-medium/

² https://www.lego.com/ms-my/sustainability/product-safety/materials

³ https://businessanalytiq.com/procurementanalytics/index/acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene-abs-usa-price-index-2/